Employers should See Potential in care leavers

My earliest memory is at eight years old, sitting on a train with my younger brother. Our uncle had alighted a few stops earlier, and there we were – two young lads, me with a bar of Bournville chocolate, my brother with a bar of Dairy Milk. As the train pulled into its terminus, we sat, watching everyone get off. The guard came and asked us what we were doing and, once our faces indicated we had no idea, the police then came for us.

The next thing I remember is sitting at King’s Cross Police Station, with everyone asking if we were ok. I still had one piece of chocolate left, and I noticed it was getting dark outside. Eventually, we were bundled into a car and driven out to the countryside to a short-stay children’s home in Enfield, where we’d be just until the authorities located our correct whereabouts.

That was in 1966. Little did I know I wouldn’t leave until I joined the army in 1975.

So how did we come to find ourselves in care? Well, our parents had come from Nigeria in the 1950s to study in the UK. When Nigeria gained independence in 1961, they were part of the diaspora of Nigerians who went back home to build the new nation.

My brother and I stayed behind. British education was highly valued at the time and my parents wanted to make the most of the opportunity for us to learn here. We went into private fostering, paid for by our parents, while my uncle – a young student – was tasked with visiting us periodically.

My experience of fostering wasn’t very good to be fair. I have to say, in most of my placements back then (I had a few), as “black children” my brother and I were valued little more than family pets; however, I know my parents were doing their best at the time. In 1967, the situation in Nigeria changed; a civil war broke out, infrastructure collapsed, jobs were lost, and soon the money stopped coming over.

Our foster parents then were based in Portsmouth, and when their payment failed to come through, they called my uncle to come and collect us. However, he was in no position to look after us and that’s how we came to find ourselves on the train that day. Apparently it was he who called the police on our behalf.

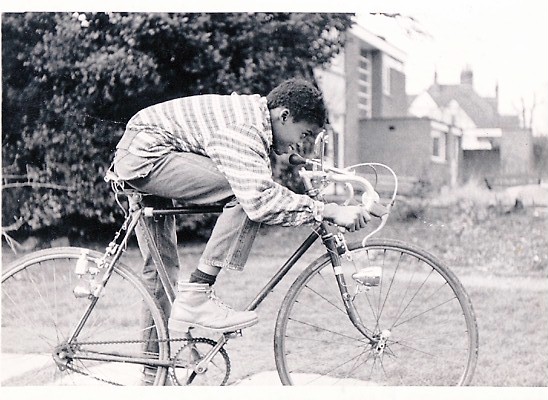

Kriss in the summer of 1972 in the children home with his first bike built by Uncle Martin.

Looking back, the experience was a traumatic one all the way along. As a child, you cope with these experiences, but you cope with them by cauterising your emotions, your feelings, your empathy with other people. Regardless of how somebody ends up in a children’s home, they will always see it as their fault. Children internalise the notion that they are the problem, doubting themselves and the world around them. It’s no surprise many mistrust adults and authority.

The traumatic thing for me was the sense of ‘helplessness’ – being unseen to the wider world, with no one person in adulthood being able to fight my corner. We had a series of placements where we were subjected to both physical and emotional abuse, and I vividly remember my survival technique of retreating into myself. I gave up on my brother when he was on the end of severe beatings, as I realised it really was a better idea to comply with the situation than rile against it. Looking back, I think this austere treatment went a long way in preparing me for the army – accepting all conditions, no matter how unfavourable.

As I approached 16, I realised things were about to change. My school was starting to give careers advice, and my friends were going off to become gasfitters, engineers, plumbers. Me? I didn’t have a clue. My friends were making these decisions coming from supportive homes with mums and dads. My biggest concern was, “Where am I going to live?” At 16, I’d need to leave the children’s home, and would most likely find myself in a bedsit, fending for myself. Now I wasn’t very mature at the time, but I was mature enough to know I wasn’t ready for that.

So I needed a career where I’d have some extra security – food, clothes, a roof over my head. I went to the army careers office, took a load of brochures and soon found myself on a weekend entrance course in Chippenham. And at 16, I left the children’s home for good.

My life was changing. I was turning a corner. I signified this with a name change – going from ‘Kezie’ to ‘Kriss’ during the course of the train journey to the barracks! I wanted to detach from that persona, that name which was synonymous with the boy from the children’s home, the prankster, the class clown. This was a fresh start and I was ready for it.

I was desperate for my new superiors to see my potential, my skills and my abilities. Shedding that old identity was a key moment for me. And the real transformation came when I met Sergeant McKenzie – a troop sergeant who oversaw our army athlete’s training. One day, he pulled me aside and said the most magical words to me: “You’ve got potential, and I believe in you.”

I believe in you! Wow – if you say that to a kid who’s been in care but is wide awake and keen to belong, I assure you, he or she is going to fly because they often won’t have had that belief at all, least of all in themselves. I love the Buddhist proverb, “When the pupil is ready, the teacher appears”, and someone who sees potential in a ‘looked-after child’ really can go on to be a teacher in their life.

From that moment, Sgt McKenzie was the one who put my nose to the grindstone and set me on the path to my future athletics career. We trained together on the moors, he developed a programme for me, he bought me my first set of running spikes.

He believed in me. He was the catalyst and instigator of everything to come. And when I began to see things in myself, I was able to go on to find the others who’d bring me on to championship level.

Barcelona Olympics 1992. Image Credit: Mark Shearman- Athletics Images.

It’s not difficult to be the catalyst in somebody else’s life. You too can be a mentor, a coach, a role model to someone who’s ready and willing to learn from you. If you’ve got somebody coming to your business who realises this is their one and only chance, that person will go to the end of the earth for you. That was me when I joined the army. I so desperately wanted to belong, to be a valuable member, to have that structure and order in my life – because I was awake to the fact I had nothing to fall back on.

That’s why See Potential is such an incredible campaign, and one I support so much. If you’re considering taking on somebody who’s recently come out of care (and they are ready to prove themselves in the workplace), I assure you, they’ll be a true asset to your organisation. All you need to do is simply see their potential, and give them the chance they’ve been waiting for to shed the stigma, the stereotypes they’ve lived with for so long. And I’m proof of just how far a person can go when their potential is recognised, coached and nurtured.

All of this ultimately dawned on me at Her Majesty’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations, when HRH Prince Harry – Prince Harry! – recognised me in the assemblage. I turned to my family in disbelief, “The little kid in the children’s home would never believe he’d be recognised by royalty one day.”

If only that boy on the train knew what was to come, what was in store for him. And all because someone believed in him.